__________________________

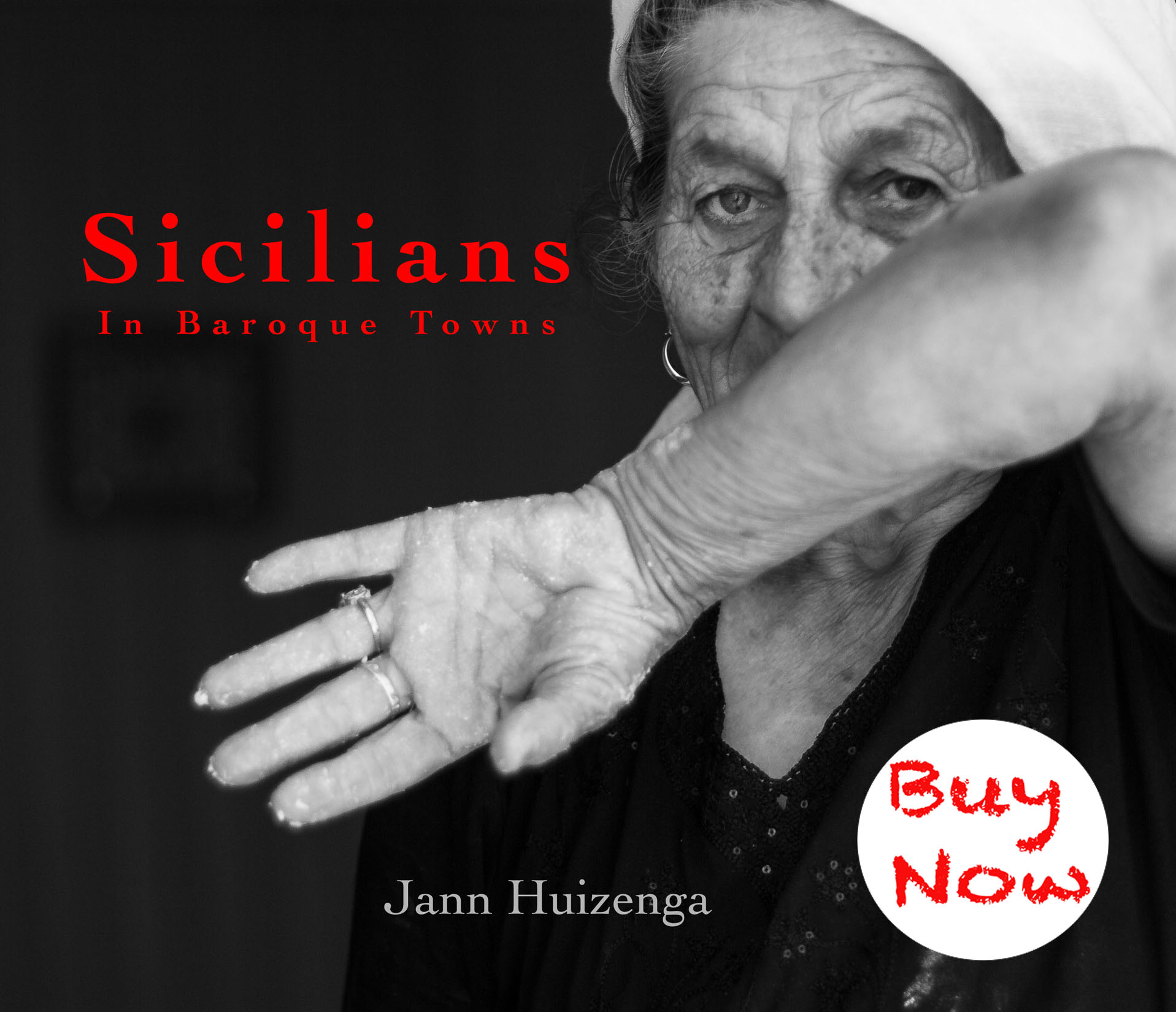

It’s the Little Things

by Jann Huizenga

Sicily reminds you what it means to be human.

On a flawless autumn morning en route to the market that hugs Ecce Homo Church, you round a bend into a narrow lane and come upon a pair of anziani, ancients, engaged in conversation. A shaft of sunlight illuminates them like a klieg light. Canes in hand, they lean into each other, their bowed backs forming a seamless arc, a human echo of the arched limestone doorway that frames them, and they’re so perfect you want to tell them—Siete bellissimi!—but you can’t really go around emoting like that to total strangers. If you look close, you can see slippers on his feet and holes in her shawl. They part as you pass. He shuffles downhill with his crispy filone under one arm as she hobbles up—perhaps to the very bakery from which he’s just come. It’s the little things that endear you to Sicily.

Then an apparition in white floats by—long white habit, white wool stole, white shoes, white socks, white bag, pearly-white digits nervously fingering white rosary beads.

A block later, you turn another corner, and—whoa!—a Rachmaninoff piano sonata comes crashing, like a breaker, over you. You come to a dead stop and lift your eyes up up up the pockmarked, lemon-pink stucco, up past the weeds sprouting from the wall, up past the doves in the nooks, and there, on the third floor of this crumbling 18th-century palazzo where the French windows have been flung wide open to the world, great piano chords soar out on the diaphanous wings of lacy, white curtains. O, joy. Who is this virtuoso? Man? Woman? Child prodigy? The music mingles with the intoxicating coffee smells from the street-level bar. You linger, jotting down the address so you can pass this way again. A block later, two blocks later, the notes are still trailing you like chi, then fading, fading, gone.

Autumn is advancing. In The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa describes this season as “the real season of pleasure in Sicily: weather luminous and blue, oasis of mildness in the harsh progression of the seasons, inveigling and leading on the senses with its sweetness, luring to secret nudities by its warmth.”

You start to climb. A thick-necked housewife with her bamboo basket and two old codgers in dark suits going arm in arm—one with a fedora, the other a capota—labor up the hill ahead of you toward the market at the foot of the old church, a sunlit confection of burnt-sugar. You catch a snatch of “Lascia Mi Cantare” and a whiff of beefy ragù. Lads with overloaded backpacks and panini in their teeth run down the hill, while a miniskirted lass on a neon scooter zips uphill, wild dark curls in her wake.

And then someone greets you: a nun begging coins for her tin can, wearing a timid smile and the wimple and habit that have gone the way of meatless Fridays back home. It’s unlucky to see a nun, Sicilians have warned, and you’ve just spotted two, so you touch the iron on your belt buckle to break the curse.

Right behind the sister, at the base of the church steps, is a lingerie bazaar—sort of an alfrescoVictoria’s Secret—with cascades of corsets and camisoles, piles of panties and pettipants. The stiff cones of the stacked push-up bras, like cupolas, point heavenward. Women are furiously slipping them on right over their clothes—shameless!—and stretching supple girdles and thongs wide against their loins, apparently not giving a rat’s ass that they’re under heavy surveillance by Romeo, the vendor lounging up there on the church steps. At €1 each, who can resist the pretty panties? You scarf up as many as you can, then trip up the church steps to foist your intimates on Panty Man, praying to God the good sister isn’t watching.

Panty Man holds your €20 note up against the sun and studies it exhaustively, as vendors here tend to do. You seize the opportunity to steal a look at him. A tanned face spattered with those inevitable Mediterranean beauty marks. Bedroom eyes. O Romeo, Romeo! A silver cross twinkles on his hunky neck.

“Va bene?” you finally squeak. Is it OK?

“Va bene, Signora,” he coos, flashing a zillion-watt smile. He gives you your change and breathes something indecipherable about … counterfeit cash? pretty panties? afternoon amore?

The market spills out into the adjacent streets. Vendors are shouting at the top of their lungs, one waving bunches of spring onions about. Shoppers are weighted down with baskets and bags and armfuls of flowers and lettuce. You catch snippets of gossip, snatches of scandal, as you dodge the crowds and duck under flapping tarps and tracksuits and tablecloths to arrive at your favorite farmer.

There are heaps of glossy chestnuts as gorgeous as they can be—”grown high up on the slopes of Mount Etna,” the contadino says. For the past week, chestnut roasters around town have been perfuming the soft evening air with the smoky-sweetish-nutty savor. The vegetables are whoppers: monumental mushrooms, freakishly-large eggplants, cauliflowers big as basketballs. The rich Sicilian loam supersizes everything. There are plump pears; zesty, thick-skinned lemons; artichokes on fat stalks; big, floppy heads of lettuce; just-picked apples with leaves still attached; prickly pears; alabaster melons; wine-red potatoes; strings of onions; peppers glowing green. And a cornucopia of pumpkins—strange nut-colored squash like the one my friend Rosaria carved out for the yummy pasta she served at her six-hour dinner last Saturday. Here’s what you do: dig out the flesh, boil it up, mash it with fried onions and ricotta, then mix in the farfalle.

I buy the mother of all fungi—a fantastical storybook carob-tree mushroom pale as the moon. It should last me a week, maybe two. I’ll sauté it to a deep golden patina in oil and onion, mushrooming the entire apartment with the aroma, then polish it off in a kind of hypnotized rapture.

“Troppo caro! Too expensive!” sniffs an old woman, rubbing her thumb and index finger together as I fish €2 from my jeans pocket. It’s her way of telling me I haven’t haggled with enough diligence.

The farmer packs the meaty mushroom into my pink string bag with his wide, chapped hands, laying it carefully in the cuddle of the pretty panties.

Onward to the fishmonger, where the funk smacks my nostrils and keeps my breathing shallow. He’s got a dazzling swordfish on ice in his truck bed. He lobs off a meaty red slice and gives me a short lesson in how to cook it: Sprinkle course sea salt in the frying pan and heat it up—without oil!, Signora. Grill the steak for a minute or so and then flip it over. Drizzle virgin oil on it only after cooking, Signora, along with a healthy squeeze of lemon. He throws in a few gamberoni, jumbo shrimp. “Un regalo,” he smiles. A gift. Sicilians must be the gift-givingest people on the planet.

At the next stall I buy a zucchini long as I am tall. The purple-nosed vendor chops it into thirds so I won’t billyclub my fellow marketers. I’ll try to make a Sicilian caponata, adding the eggplants, onions and tomatoes that my friend Mary has plucked for me from her husband’s garden.

Three long tables display mounds of small cotton rugs from India, Turkey, and other parts of the globe. “Prego, Signora! Only €4!,” calls a vendor with a voice like a castrato and a Sicilian schnozz—imagine the beak of a Pirandello, DiMaggio, Zappa, or Scorsese. I finger an ivory rug made in Sardinia—Sardegna!—a sister island I’ve yet to set eyes on, but whose golden syllables are so magical, so redolent of uh … oh, I dunno—sardines?

Then on to a table brimming over with towels. I shoulder my way into the clump of women and locate two dish towels for €1 each. “These will dry your dishes very well, Signora,” says kind-eyed Towel Lady, nodding her approval. “You will be happy with them.” Into my string bag go her lovely cotton towels, and I wonder why I feel hyper-alert when marketing here while I sleepwalk at home. What a humanizing antidote this is to big-box stores, which seem, somehow, to diminish life.

On to the fig-nut-legume man, where I buy a sack of praline peanuts. “And are these lentils?”

“No, they’re split peas, Signora.”

“Buonissimi!” shouts the stout woman next to me, planting a loud kiss on her bunched-up fingertips and then splaying them out in a burst like an exploding sparkler. They’re wonderful!

“Oh, really?”

“Sì, sì.” She nuzzles closer and says conspiratorially, “Put them in your minestrone. And you should add chopped onions to your brodo … and carrots, some potatoes … celery, cabbage … tomatoes, beans, zucchini—”

“Grazie, mille grazie, Signora!” I say, cutting her off politely. Strangers in Sicily, sensing that I don’t know the ropes, are veritable fonts of unsolicited opinions, advice, and very loooong recipes. I point at two drums of peanuts and ask what the difference is.

“The small ones are local, Signora. The big ones come from California.”

“Well, since I’m American, I should get the local ones.”

He beams, shells a few peanuts and drops them into my hand. “Our local ones are better. Pù gustoso. Tastier.”

The Old World graciousness in these simplest transactions reminds me what it is to be human. People connect. No automatons here. An unwritten rule in Sicily is to make meaningful eye contact in all encounters. I see neither the expressionless American eyes that look over your shoulder or down at the ground, nor what Frenchman Bernard-Henri Lévy, in American Vertigo, calls our “affectless, emotionless smiles.” Sicily stirs my dormant humanity.

Into my bag go the small local peanuts, the split peas for minestrone, and the pralines, which beg to be eaten before making it home.

I pass prodigious mounds of black olives—a bumper crop this year—then stop to chat with the slipper-and-socks man from North Africa. Sicily is gearing up for winter; the man’s got a stock of thick, gray, woolen panty hose—the Sicilian equivalent, it appears, of long underwear. I ask about slippers.

“Ha la 38?”

“No, Signora, only one size left.”

“Where are you from?”

“La Tu-ni-si-a.”

“O, che bello! I was there many years ago.”

“Where did you go?”

“Tunis, Sousse—”

“I’m from Tunis.”

“Oh, really. Uh…may I take your picture?”

“No, mi dispiace, Signora,” he says with a fleeting look of panic. “But do you want to take a photo of my slippers?”

A smiley tomato vendor—a leather-skinned showman in a blue baseball cap—spots my camera and motions me over. He mugs behind a fiery pyramid of the fleshy fruit, and then I buy a kilo of tomatoes that I don’t need.

“Come ti chiami?” he asks with Sicilian curiosity. What’s your name?

I introduce myself and he sings a snippet of “Love Me Tender.” I ask his name.

“Piero Piccione.” Peter the Pigeon.

Such evocative names in Sicily. I’ve met Mary Christmas (Maria Natale), John the Baptist (Gianni Battista), Johnny Cinammon (Gianni Cannella), Mrs. Horse (Signora Cavallo), Mr. Money (Signor Denaro), Mrs. Dry Valley (Signora Sechivalle), and Hector the Onion (Ettore Cippolla).

“Sei sposata?” he asks. Are you married?

“Sì.”

“Con bambini e tutto?” With kids and everything?

What a funny way men here have of interacting with women. I lie and say I’ve got kids. I don’t want to incur one of those sorry looks that Sicilians bestow on child-free women.

Piero gallantly tucks a free finocchio, fennel, into my bag. Sicilian fennel almost knocks you out with its heady anise aroma. A man with white hair walks by. He picks up another feathery bulb, winks, then presents it to me. “Un regalo,” a gift. “You don’t pay for this.” He and Piero laugh.

I look at my watch. Five to eleven. Time to run. I have a rendezvous with my Japanese friend, Reiko. Piero and I shake hands.

“Per favore, bring my photos next week!” he

calls after me.

Arms overflowing with market booty, I head for the Caffè Mediterraneo via back streets, where the cracked walls are bulletin boards of death. The notices—black-bordered papers called necrologie—are plastered everywhere. CIAO NONNO GIORGIO says one poster with a photo. Goodbye Grandpa George. My friend Mary says she was “freaked out” by the “morbid things” when she first arrived in Sicily, but I think they have a spooky beauty. They celebrate you all over the neighborhood for months, even years, while all we get is a tiny blurb for a day on a newspaper page no one reads. “You’ll be a better person if you think about death,” goes an old Sicilian saying. The necrologie are a constant reminder to mend your ways.

The terrace of the caffè—Ragusa’s swankiest—looks like a casting call for film noir villains, but the players are just staid burghers puffing on cigarettes, all decked out in shades and crocodile shoes, buttery briefcases, cell phones on ears. Ah, there’s my landlord, Giorgio, a social gadfly who, as Mary puts it, “is more common than Coke.” I wave and head indoors, where the women hang out.

“Buon giorno, Signora!” the barista calls out, lavishing me, like all his customers, with a royal welcome that feels like an embrace. I’ve arrived late, of course—having begun a slow but inexorable slide into the Sicilian Time Zone. Coltish Reiko exhales audibly when I sit down. In a place like this, a lone woman draws unwelcome attention. Now that we’re a twosome, the gongoozlers belly back up to the bar and resume their scheming. Reiko orders a hot chocolate, which arrives pudding-thick, with two rococo meringues on the saucer. The solicitous barista has fashioned the pillowy crema of my cappuccino into a gorgeous heart. If the test of beauty, as someone once said, is the measure of joy it brings, then this is one dazzling cappuccino! Butter cookies I haven’t ordered appear from nowhere—each topped with a different prize in the center—a coffee bean, a crimson cherry, a piece of chewy fig. How they prettify life here, pass the love around. Even the sugar packets have poetry on them.

Sicilians slug their coffee, but I linger over mine, taking tiny sips, while Reiko gives me an update on her Bolognese beau to a background of startlingly merry mobile ring tones. They’re planning a summer wedding. “Fortunatamente,” she says in Italian, “Lorenzo doesn’t have narrow views about women like some Sicilian men do, and he’s encouraging me to work. But finding a job in Bologna is hard. No one answers my e-mails.” I tell her she needs to put in an appearance, something I learned recently from Mary when she was driving around the province delivering her résumés. I asked why she didn’t just e-mail them. “That would be useless,” Mary said. “Potential employers in Italy need to see you; you’ve got to butter them up in person.”

The barista fawns over us, practicing his English. Is coffee good? You like cookies? You like more? You like Sicily? Sicily men good? I am Giaccamo—James, like James Dean.

In Together Alone, Calvin Morrill argues that “fleeting relationships,” though short-lived, are “colored by emotional dependence and intimacy.” Sicilians, in contrast to Americans, seem to have perfected the art of making ephemeral attachments as lush as they can possibly be.

Reiko is leaving for Bologna tomorrow, but we agree to meet again next week. We gather up our bundles and pay the cashier. The hearty Buona giornata! we collect from the barista on the way out the door feels like a winning lottery ticket.

Jann Huizenga has lived in Sicily on and off since 2002 and is at work on Kissing Sicilians: My Life in Ragusa, Sicily. This story won the Gold Award for Travel and Shopping in the First Annual Solas Awards and appears in 30 Days in Italy, second edition.