November 9, 2013

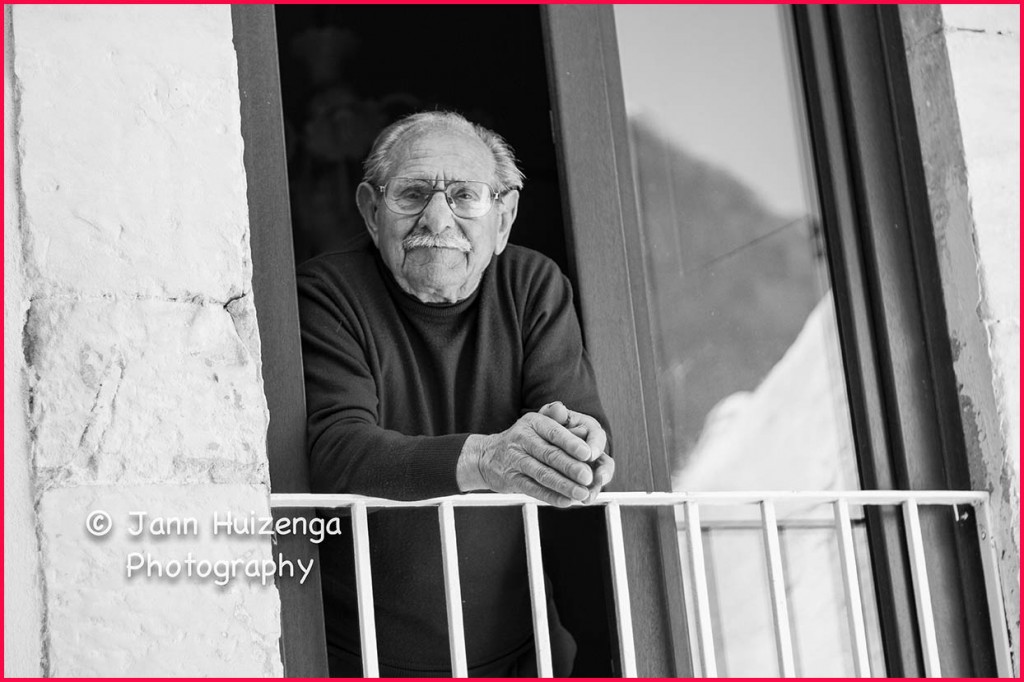

In my last post, I mentioned my 95-year old friend Salvatore.

The first time we met, he poked his head out the window to see who was in the tiny piazza under his window. We chatted. I craned my neck up and dried pigeon poop crackled beneath my feet. He told me he was the second oldest person in the village, and I asked if I could come up.

In his kitchen, I ask about life in the village 50 years ago. But he wants to talk about the war. He remembers it like yesterday.

In 1940 I was drafted into the Italian army. I was first stationed in Tripoli and Algeria for about 6 months. Most of the time was spent in the desert. There was sand, sand, always blowing sand. I was a driver. They gave me a special leave for 15 days to come home and get married in 1942. After Africa they sent me to Yugoslavia, in the Ljubljana area.

In June 1943 my captain told me I could go home. I traveled across the Adriatic by ship to Messina and then found a trucker to take me to Siracusa and checked into a hotel, with a plan to take the train to Ragusa the next day. At exactly midnight on July 10, 1943, the air raid sirens woke me up, and the American bombardment of the marina started. It was the start of Operation Husky. We all ran into a rifugio in the basement of the hotel and stayed there the whole night. When I went to the train station the next morning, it was not there. It had been bombed to the ground. So I walked to Floridia, where the rail line was still good. I was dying to see my wife and family. I was still dressed in my soldier uniform. An old horse-drawn cart (carretto) with a family inside approached and they agreed to take my luggage. The cart stayed on the road and I walked across a field. I crested a hill and was swarmed by British soldiers. They pointed their guns at me and I put up my hands. They took me to a concentration camp at Cassibili, about 10 km outside of Siracusa.

The Americans were advancing day by day and every day the British let a few of us Sicilians go home. “You will be released tomorrow,” they told me one fine day.

But on the very day of my release, a counter-order arrived: ALL SICILIAN PRISONERS ARE TO BE PUT ON A OIL TANKER AND SENT TO ENGLAND.

The men who were left in the Cassibili camp, about 150 of us, were marched into the hold of an oil tanker, along with some prisoners from other camps. How it stank of petrol down there in the hold! Not too far out of Siracusa, the Germans bombed us and the tanker split in two. I found a lifejacket and floated in the water from about 10am till 6pm, when an American ship spotted us and sent out little lifeboats to pick us up. Of the original 220 men on the boat, only 80 or 90 survived. I was one of the lucky ones. All the rest, dead. The captain was a good man. He gave us whiskey to warm us up.

The ship took us to Algiers, and from there we had to walk 60 kilometers under the hot sun to a concentration camp called Campo Costantino. No water in the July sun in the desert, and no food. We arrived there around 7pm after having walked the whole day. Not everyone made it, though. Once in a while we heard a BOOM! Someone had fallen because he could no longer walk, and was shot. Who shot the men? It was Indians. You know, the Brits, Americans, Indians–they were all Allies.

Of course, we were hungry when we arrived. Avevamo un fame terribile. They gave us 15 pieces of maraconi to eat, each the size of my thumbnail. Pasta vuota in brodo, basta, nothing more. We went into the kitchen. Is there more food, we asked? No. Avevamo un fame incredibile.

They made us sign papers: Sono prigioniere italiono dagli inglese. In Campo Costantino. They sent this to our families. We stayed only one night in this camp, and then we had to march back to Algiers.

Where they put us on another ship, the Queen Mary. What a beautiful boat! When we went to dinner we found proper silverware–real silver!! And cloth napkins. We’ll eat well here, we said to ourselves.

But we were always hungry. For dinner, we sat at a table of 13 men. Six on each side and me at the head of the table, since I was a sergeant. The first night, after we waited an hour, they called me into the kitchen and gave me a pan of macaroni and I divided it absolutely equally. I remember clearly: I gave each man 12 and a half tiny pieces of macaroni, no bigger than a fingernail (he shows me his pinkie). We starved on that ship. Imagine having all that fancy silverware and nothing to eat! (Salvatore smiles.)

There was a pantry full of food, guarded by two sentinels. One night we killed them. How, you ask? Col cotello! With a knife! We threw them into the sea, and then went into the storeroom and gorged on cans of meat, tuna, and biscotti.

The next day, of course, the British were looking for their sentinels.

C’era un silenzio totale.

They understood we had killed them, and from then on, they gave us nothing but bread and water on that queen’s ship.

We finally arrived at Liverpool after 10 days. There was a big table full of food. I took 2 portions, though they yelled at me. The last two years in the camp were quite good. We could go out of the camp. British women loved Sicilians. They always said, You are Sicilian? Come on, then. They called us Uomini Gallo, Rooster Men.

Salvatore says he harbors no grudges against Britain, and even has a photo of London on his kitchen wall.

***

Fascinating story and Salvatore, you are blessed to have lived this long and through such horrible circumstances. I wish you many more happy years!

Thanks for your comment, Gil. Glad you enjoyed reading.

dear Jann grazie infinite per questa testimonianza!

I found myself working sometimes about the WWII tours about what happened during the Operation Husky i Sicily with English and American people but the memory of the locals are of a great value…

I read and read again your post and..mi sono commossa tanto..

My parents were just children during the bombing and the British landing in Sicily … un abbraccio

Lucia, I’m so glad you enjoyed Salvo’s story. So much happened around Siracusa. xxxxx 🙁

Thanks so much for your rendition of Salvatores’ story. It really puts a new perspective for me, on the wizened faces I see every day here in Calabria. As I look out over the straight of Messina, seeing the cruise ships, tankers and container ships pass by I often wonder what it must have been in times past. No cruise ships but tankers full of hungry prisoners. Puts a different outlook on the crisi. If they could live through the war, then the crisi shall pass too. Thank you for your delightful blog, I thoroughly enjoy your authentic representation of everyday life in Southern Italy. Ciao.

Joanne, thank you for this thoughtful comment, and I’m so glad to have a reader from the hills of Calabria!!! I can almost wave to you. You’re so right about the crisi–all things are relative, and it’s always good to give things a historical perspective. I hope you’re enjoying life in Southern Italy.

What an interesting story. It brought memories of tales told by my mother who was 9 years old at the time of the Siracusa’s bombing when they both had to rush to the bomb shelters as fast as their feet could carry them. I listened raptly to the stories and to this day I vividly live them in my mind as if I had been there.

Carmela, thank you for this memory. She and Salvatore must have been rushing into the bomb shelters at the same time in the same city. And welcome to this blog!!

This war generation got around in the world quite a bit.

That’s for sure, Andreas! And the Maltese were the unsung heroes.

Ciao Jann, I have just stumbled onto your blog through Lisa Chiodo,who’s Renovating Italy, I have been following for a while.

Loved your story….I visited Sicily in april with my daughter ,for 16days. It was 110yrs since my grandfather and his family left Trapani..so a bit of a pilgrimage to the land of my ancestors…..Hopefully the first of many visits

Ciao Sandra–how delightful about your pilgrimage to Sicily! And that you could do it with your daughter. So glad you found me here, and thank you for reading and commenting.

A very special story. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you Ellen. Welcome to this blog!

O my goodness Jann….. I wasn’t expecting this. Just think of the stories we all pass in the street everyday. I love the direction you’re taking the blog. Like a real sense of you honouring your adopted home. Complimenti! xx

Everyone is bursting to tell a story, don’t you think? So glad you stopped by, Janine, and thank you.

What a fascinating story! He does not look 95! No wonder the ladies loved him!

He is the friendliest guy, and I think his secret is sitting on the piazza all morning sipping strong espresso and watching the world go by. That’s how I plan to spend my 90s. 🙂

I just finished reading “The Day of Battle”, the war in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944 by Rick Atkinson. What a mind opener. It told of the horrors all the men from all the countries suffered .Salvatore’s story is one of thousands told, but probably forgotten. Thank you for telling his story. Happy 95th year to you Salvatore, your strength and kindness show on your face. May we all be reminded what war brings to all of us.

Vicki, I’m so glad you mentioned & recommended Rick Atkinson’s book. My husband has read it and raved. Thanks for your kind words to Salvo.

Unbelievable story. so much uneccessary bombing.

Yes, so much bombing. My “cantina”–lowest floor–was my neighborhood’s rifugio. Thank goodness there were, in the end, no bombs dropped on Ibla, but plenty elsewhere.

Wow! What a brilliant story of courage and endurance. My regards to Salvatore. His story and fine looks at 95 are very inspiring. Something indomitable there. Thank you for sharing his story, Jann. I’ve got only one question: what other tales does he have? xx

Narelle, I’m sure he has other tales, and I’m going to pull them out of him. 🙂

Jann…always marvellous.

Ciao Marisa–missing you here! Come back soon. xxxxx

I looked a long time into the eyes of Salatore. He appears to me to be a person who is satisfied with his life. I’m glad he survived his ordeal as he seems to be very aware of his humanity. Bless him.

Hi Tom–such an interesting comment!! I have to agree with you. Maybe that’s why he’s living so long. He is upbeat, engaged, and happy. And may I add very lucid. Welcome to the blog!

With regard to the Italian military during WWII, historians seem to agree that their hearts weren’t really in the fight. They mostly wanted to get back to their women, wine, and pasta.

That’s certainly the feeling I get from Salvatore. He just wanted to go home to his wife.

Ciao Jann, Salvatore looks like my late Uncle, Joseph Schinina who died a few years ago in Ragusa I believe in his late 90’s. You know here in the States they always talk about health and how lucky we are to have great Health care, but if so, why do we die much earlier then the Ragusane, I suspect all the wonderful things Ragusa has, we are missing, Clean Air, Natural Foods, and a much quiet life with less stress, who know’s, maybe I’m wrong, but I’m sticking to this story.

Lucky you

Many say it’s the olive oil, John :). Also, less stress, fresh food, family bonds, community bonds? Super-clean air I’m not so sure about since ENI petrol companies installed themselves on Sicily’s shores. 🙁

What a moving and entertaining tale. What a man !!! Thank you for sharing his story.

Many thanks to you Caryl for commenting. Welcome to the blog!

As we escaped the second world war by the skin of the teeth in spite of the great effort of sir Winston Churchill who had a meeting with İsmet İnönü, the prime minister of Turkey at the time to move Turkey to their side against Hitler and his partner Mussolini, we only have few veterans that participated Korean wars that took place in Kunuri mostly in 1952 and the only living person left from the War of Independence in 1919-1923 died recently at age 105.So your telling us this big man’s war story is to be documented by Italian authorities as well.You did a nice job, Jann. An incredible time for a young Sicilian lad who is fortunate to stay alive.

I didn’t know that Churchill was trying to get Turkey involved. Lucky for Turkey that didn’t happen! Yes, the voices from that war are dying out now. Thanks, Cemal, for always adding an interesting historical/cultural perspective! xxxxxxxx

Wow! What a great story. Thanks for sharing it with us. We just had a Veteran’s Day assembly at school on Friday. I think our fifth graders should hear Salvatore’s story.

Good to get a varied perspective, I think.

Are you going to edit the part where they kill the 2 people guarding the food and throw them overboard? for the 5th graders

Interesting question, Sam. What do you think she should do?

Caterina, it’s odd that I put out this blog about an Italian vet right before Veterans Day in the US. I wasn’t even (very) aware that it was coming up. Today, Nov 11 is the day of San Martino, a day for drinking new wine and eat fritters called fritelle. Well that would be great if you’d tell your 5th graders about Salvatore’s experiences from the “other” side.

Jann, thank you so much for making the effort to interview this gentleman and share his tale with us. We have it so easy, not living under the constant threat of war here. Sadly, that’s not the case for many places around the globe. Only by keeping alive these stories of suffering and survival do we have any hope of finding a lasting peace.

Debbie, thank you for reading and commenting. You’re so right. xxxx

What an absolutely incredible story Jann. And he must have loved having a captive audience recording it! Thank you.

He did seem to enjoy the telling, Cathy!

So good to read Salvatore’s story,in his own words. Thankyou for documenting it.We sometimes forget how terribly difficult life was for most Italians throughout the period of WW2. A handsome chap too!

Ciao Francesca. You’re right–Italy, and Sicily in particular, have changed so much since WWII that it takes a story like this to remind me of what the older folks have been through, and can still remember so clearly.

what a story! enjoyed reading every line. xxpeggybraswelldesign.com

Many thanks for stopping by to read and comment, Peggy. It’s always a pleasure to “see” you. xxxx

Great story, thanks for sharing.

Ciao Ron and I thank you for reading.