January 30, 2010

I hire a team of architects.

I fire a team of architects.

I leave my husband in New Mexico and take a job in Rome in order to be “close” to Sicily.

And, oh, what a job it is (why don’t I have any luck with Italian bosses?).

The whammies start to add up.

I hire a project manager (the handsomest of men) with a swagger, cool sunglasses, a Range Rover, a mop of curls, an Etna-like temper and—how best to put this?—a hands-off management style. Which I only learn later. His mantras are Non sono d’accordo and Non e possibile.

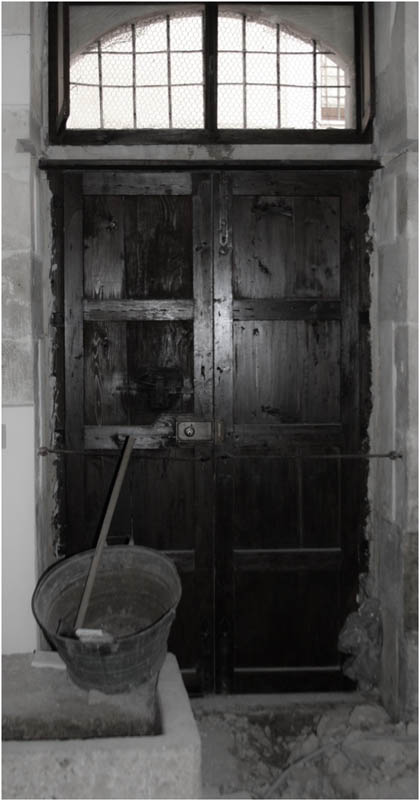

My Roman job swallows me whole, but on rare occasions I sneak down to Sicily to prod, cajole, wring my hands, and gnash my teeth. I prowl around the damp house—it’s twice as cold inside as outside—and wonder how it’ll ever be livable. Why in the world is the building permit taking so long?

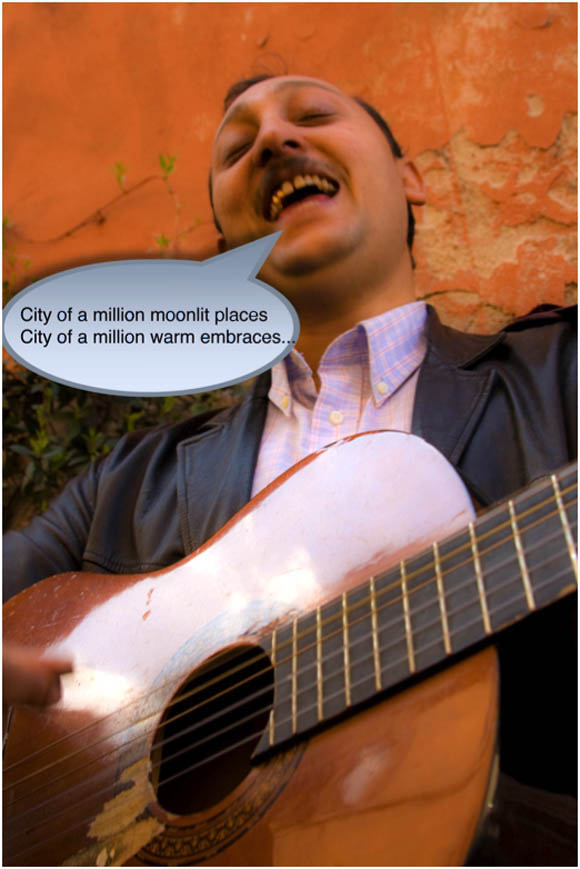

Pazienza, Sicilians tell me. I’m not a patient person, but I’m beginning to suspect I’ll need some endurance to get the life I want to lead.

What is the life I want to lead, anyway?

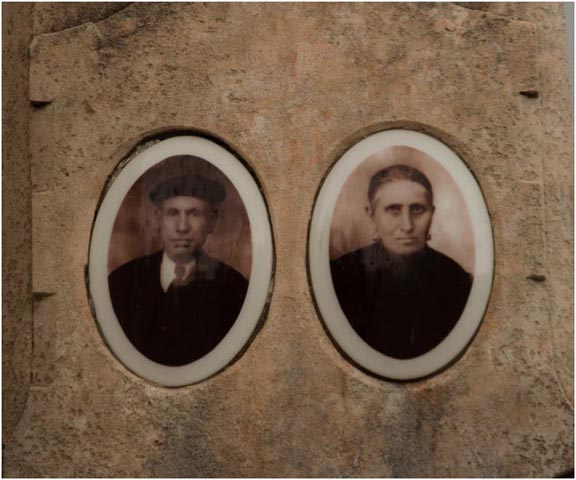

A stop-the-world-I-want-to-get-off life, a turn-back-the-clock-a-century life. A new life. A second life.

A friend forwards an email from a British guy who is temporarily living in Italy: “Anyone buying any kind of property in Italy needs counseling. I send my deepest sympathies to the lady in Sicily…”

New Roman friends respond with audible gasps, like in a comic book, when I tell them I’m renovating a house in Sicily. They call me coraggiosa and then laugh themselves silly.

My husband remains reluctant, though not opposed.

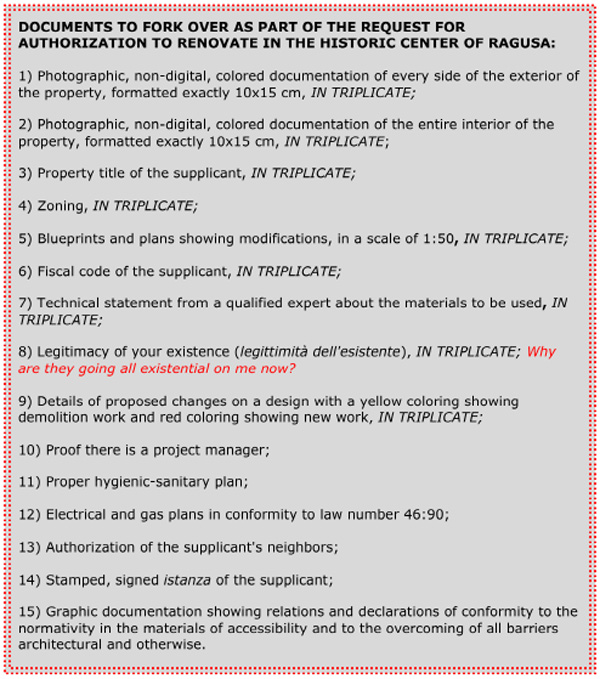

Lo and behold, 8 months after I buy the damp old house and after endless phone calls, faxes, and DHLs (my project manager avoids email), I am in possession of a building permit. The legitimacy of my existence is confirmed.

“It’s your Christmas present,” says my best friend on the island, an expat Sicilian-American upon whom I lean like a crutch.

Never mind that the dollar is at an all-time low. Or that our retirement nest egg is about to dissolve like salt in water. Or that I feel I’m flying off a cliff.

Let the work begin.