November 9, 2013

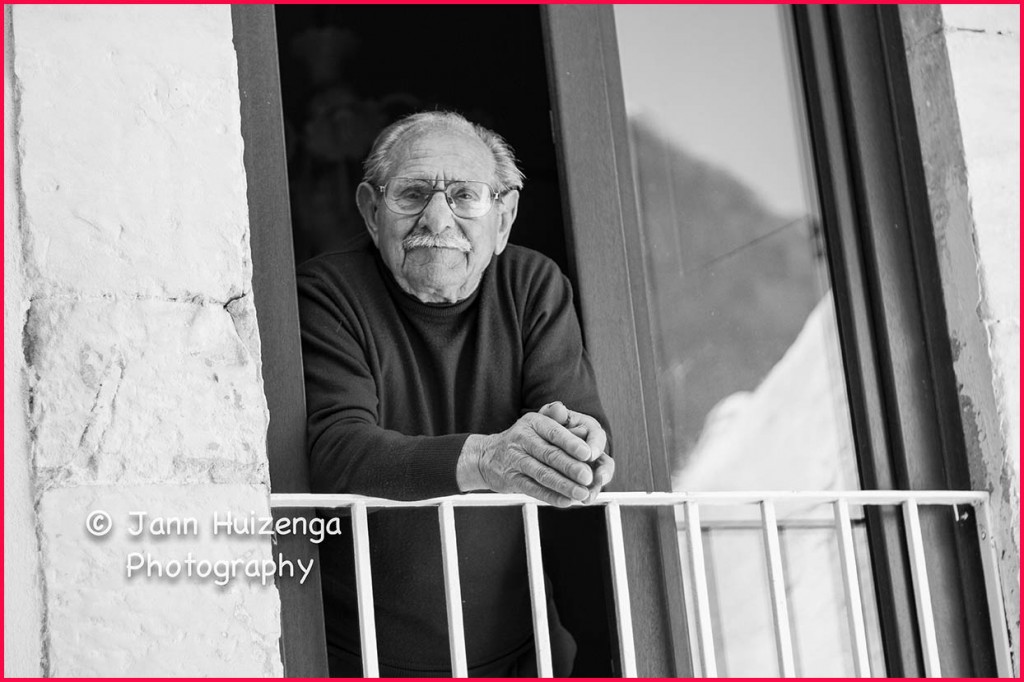

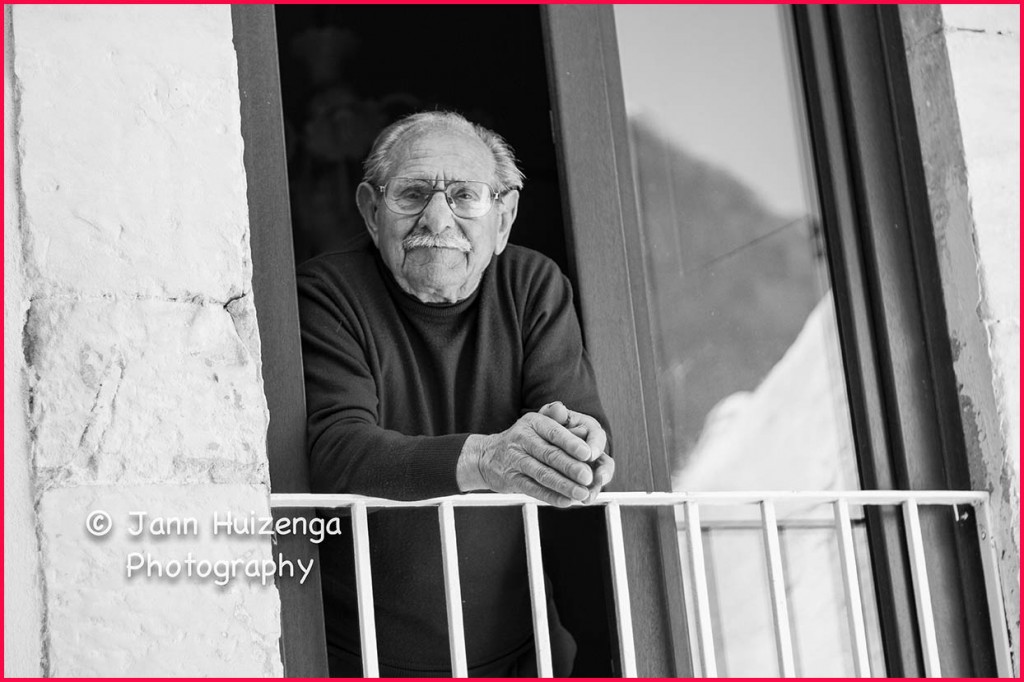

In my last post, I mentioned my 95-year old friend Salvatore.

The first time we met, he poked his head out the window to see who was in the tiny piazza under his window. We chatted. I craned my neck up and dried pigeon poop crackled beneath my feet. He told me he was the second oldest person in the village, and I asked if I could come up.

In his kitchen, I ask about life in the village 50 years ago. But he wants to talk about the war. He remembers it like yesterday.

In 1940 I was drafted into the Italian army. I was first stationed in Tripoli and Algeria for about 6 months. Most of the time was spent in the desert. There was sand, sand, always blowing sand. I was a driver. They gave me a special leave for 15 days to come home and get married in 1942. After Africa they sent me to Yugoslavia, in the Ljubljana area.

In June 1943 my captain told me I could go home. I traveled across the Adriatic by ship to Messina and then found a trucker to take me to Siracusa and checked into a hotel, with a plan to take the train to Ragusa the next day. At exactly midnight on July 10, 1943, the air raid sirens woke me up, and the American bombardment of the marina started. It was the start of Operation Husky. We all ran into a rifugio in the basement of the hotel and stayed there the whole night. When I went to the train station the next morning, it was not there. It had been bombed to the ground. So I walked to Floridia, where the rail line was still good. I was dying to see my wife and family. I was still dressed in my soldier uniform. An old horse-drawn cart (carretto) with a family inside approached and they agreed to take my luggage. The cart stayed on the road and I walked across a field. I crested a hill and was swarmed by British soldiers. They pointed their guns at me and I put up my hands. They took me to a concentration camp at Cassibili, about 10 km outside of Siracusa.

The Americans were advancing day by day and every day the British let a few of us Sicilians go home. “You will be released tomorrow,” they told me one fine day.

But on the very day of my release, a counter-order arrived: ALL SICILIAN PRISONERS ARE TO BE PUT ON A OIL TANKER AND SENT TO ENGLAND.

The men who were left in the Cassibili camp, about 150 of us, were marched into the hold of an oil tanker, along with some prisoners from other camps. How it stank of petrol down there in the hold! Not too far out of Siracusa, the Germans bombed us and the tanker split in two. I found a lifejacket and floated in the water from about 10am till 6pm, when an American ship spotted us and sent out little lifeboats to pick us up. Of the original 220 men on the boat, only 80 or 90 survived. I was one of the lucky ones. All the rest, dead. The captain was a good man. He gave us whiskey to warm us up.

The ship took us to Algiers, and from there we had to walk 60 kilometers under the hot sun to a concentration camp called Campo Costantino. No water in the July sun in the desert, and no food. We arrived there around 7pm after having walked the whole day. Not everyone made it, though. Once in a while we heard a BOOM! Someone had fallen because he could no longer walk, and was shot. Who shot the men? It was Indians. You know, the Brits, Americans, Indians–they were all Allies.

Of course, we were hungry when we arrived. Avevamo un fame terribile. They gave us 15 pieces of maraconi to eat, each the size of my thumbnail. Pasta vuota in brodo, basta, nothing more. We went into the kitchen. Is there more food, we asked? No. Avevamo un fame incredibile.

They made us sign papers: Sono prigioniere italiono dagli inglese. In Campo Costantino. They sent this to our families. We stayed only one night in this camp, and then we had to march back to Algiers.

Where they put us on another ship, the Queen Mary. What a beautiful boat! When we went to dinner we found proper silverware–real silver!! And cloth napkins. We’ll eat well here, we said to ourselves.

But we were always hungry. For dinner, we sat at a table of 13 men. Six on each side and me at the head of the table, since I was a sergeant. The first night, after we waited an hour, they called me into the kitchen and gave me a pan of macaroni and I divided it absolutely equally. I remember clearly: I gave each man 12 and a half tiny pieces of macaroni, no bigger than a fingernail (he shows me his pinkie). We starved on that ship. Imagine having all that fancy silverware and nothing to eat! (Salvatore smiles.)

There was a pantry full of food, guarded by two sentinels. One night we killed them. How, you ask? Col cotello! With a knife! We threw them into the sea, and then went into the storeroom and gorged on cans of meat, tuna, and biscotti.

The next day, of course, the British were looking for their sentinels.

C’era un silenzio totale.

They understood we had killed them, and from then on, they gave us nothing but bread and water on that queen’s ship.

We finally arrived at Liverpool after 10 days. There was a big table full of food. I took 2 portions, though they yelled at me. The last two years in the camp were quite good. We could go out of the camp. British women loved Sicilians. They always said, You are Sicilian? Come on, then. They called us Uomini Gallo, Rooster Men.

Salvatore says he harbors no grudges against Britain, and even has a photo of London on his kitchen wall.

***

Click to subscribe to BaroqueSicily.

Find me on Facebook.

My photography website.

In person, statuesque Cleo is nearly the size of a toilet bowl, and made of similar material. (Come and get her if you live nearby!)

In person, statuesque Cleo is nearly the size of a toilet bowl, and made of similar material. (Come and get her if you live nearby!)