December 28, 2010

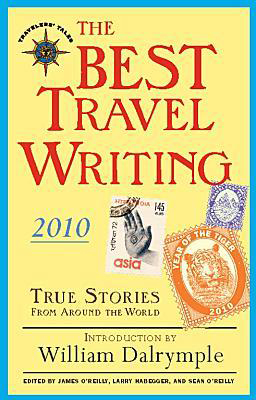

Before 2010 gives us the slip, I’d like to share a true story published in this 2010 Travelers’ Tales anthology. My Roman Reality Show is based on the 10 months I spent in Rome a few years ago while trying to situate myself in Sicily. The story shows a small slice of my life during that time–what I witnessed from my apartment window in Rome. Happy reading!

xxxx

xxxxx

xxxxx

XXXXX

XXXXX

XXXXXXXXXX

My Roman Reality Show

The TV sat dark in my Rome apartment. I spent all my spare time at the window studying the players on the piazza—the Gypsy, the Sweeper, the Cat Lady, the Reader, the Abuser, the Santas and the Sentries—always those ominous Sentries.

The night of my arrival in early September, a torrid wind blew the scent of oven-baked dough through the open window, along with the wheezing melody of “My Way.” I stared at the Gypsy with a jaunty straw hat and a cigarette pinched between his teeth. He sat outside a pizzeria pushing and pulling a red accordion like taffy over his fat paunch. A bright moon sailed overhead.

The next morning, after a night of Roman revelry, my piazza brimmed with trash. The Sweeper turned up in orange plastic pants. She raked a broom over the black cobbles like a toothbrush on rotten teeth. Then she fished out her cell phone and plunked down on a stone bench for a gabfest, as she’d do most mornings for the next ten months.

I watched a stray dog lap from the fountain—one of those big-nosed fountains (nasone) with no turn-off valve that Rome is famous for. The dog trotted off when a woman shuffled over in fuzzy pink house slippers to fill a plastic bottle. The sun bounced off luscious walls that made me think of Italian ices: mandarin, citrus, and melon. I inhaled the jasmine that framed my window and counted seventy-five other windows overlooking the piazza.

As September rolled along, the Cat Lady—the self-anointed concierge of the piazza—and I took each other’s measure. We lived on the primo piano in opposite buildings, in such proximity that we could have played catch with a ball of mozzarella. She spied on me and I peeped at her, though we never made real eye contact. I suppose she’d describe me as a lonely straniera who hung from the window shouting gibberish into a telefonino. She tossed breadcrumbs to doves and kept order on the piazza by waggling a finger at littering tourists and illegal parkers. Both she and her fat pussycat had poofs of gray hair and spent their days at the window ledge nuzzling and grooming. The cat would lick her fingers clean, and she’d brush him with long, slow strokes. Hairballs somersaulted like tumbleweed across the piazza, into the melted goo of abandoned ice cream cones.

Every ten minutes or so, there was a sudden rush of Romans into the piazza from the Cavour subway exit a block away—men in sleek suits and cool shades and perfect women in tall, pointy, clacking shoes. They rode in on a powerful tide and then ebbed away, dissolving into the many tiny alleyways radiating from the piazza.

Late at night, young men would drink beer and unroll sleeping bags on the hard stone benches, stuffing backpacks under their heads as pillows. They’d crawl away each morning when the Sweeper poked them with her broom.

In mid-October I began to notice the Sentries. The first one I spied was a swarthy smoker—Turkish or Tunisian, I thought—wearing a hooded parka, an odd getup given the warm weather. I tried to focus on my computer screen but the Sentry kept drawing me back to the window. He sat hunched on one of the stone benches, flipping through La Stampa and checking his watch, but mostly staring fixedly to the west. After an hour of this, I poked my telephoto out the window. I felt quite certain the carabinieri might someday need the evidence. What was the crime? I didn’t know yet. Click. Click. Click. He raised his eyes. I scooted behind the curtain and into the kitchen. When I returned with a mug of hot coffee he was gone.

Another soon took his place—a wiry man with icy eyes who could have been a brother to Putin. He stood by the fountain looking in the same direction, lighting up, drawing hard on a cigarette, then throwing the butt over his shoulder. Ninety minutes passed. I snapped another photo then went to the kitchen for tea. When I returned, he too had vanished.

These same Sentries kept returning, but so did Chinese, Central Asian and African men, most of whom parked themselves on the same stone bench and stared west. Who were they? I became obsessed. When they raised their eyes slightly, I began to worry that they were onto me.

In November, the Reader—a slender girl with platform shoes—began appearing on a stone bench. Like a heliotropic flower, she’d turn up for an hour of afternoon sun, a bit later each day as fall wore on. She’d fish her glasses from a bag, open a hefty novel that she held on her lap like a brick of gold, and sit ramrod straight, lost in a fantasy world, her silky black hair draping her cheeks like drawn curtains. The sun crawled low against the sky as she read, and when it slipped away, she did, too.

It was Roman men, not women, who would pause to primp in the side mirrors of parked motorini. Italian newspapers reported that Italian men were vanitosi, vain, mammoni, mama’s boys, and came in last as amante, lovers, in some recent UK survey.

In early December, a crew of young workers—Romanian? Albanian?—pulled up the cobbles to lay down pipes. They worked much harder than Romans and wore sweatshirts that said Yale, or Notre Dame, or Michigan. The Santas arrived in December, too—not one, but a quartet of them, in single file. The lead Santa blew on a trumpet while another bawled a cheery “Buon Natale!” that boomeranged around the piazza like an Alpine yodel. I hung out the window and when they shouted for a donation, I tossed it into an elastic red pouch.

One day in mid-January, after days of cold rain, a ray of sunlight sliced a black cloud to flood the piazza with yellow.

Don’t let the su-u-un go down on me…

I ran to the window. The pizzeria had put its speakers out on the street. Elton John’s voice poured like old wine through the piazza, drawing radiant faces to every window. I inhaled meaty odors and felt wildly happy.

One morning in March, I heard the Abuser. After a terrible rant, flesh smacked flesh and then a thick high whimper pierced the piazza. I knew her as the frail woman who tended window geraniums on the secondo piano opposite me. Neighbors hung from windows as if from theater balconies. It went on forever. I rushed around looking for the phone book then flipped through it until I landed on a numero azzuro, a blue number, to report child abuse. By the time I dialed, the piazza had gone eerily quiet. The operator could do nothing, she said, no child was involved. At the police station the next day, I was handed a number to call for domestic abuse. I kept it by the phone for future reference. But within a few weeks the Abuser’s windows were shuttered tight, his geraniums dead.

One morning in April, I awoke early and looked out the window. A large suitcase, open like a book, had heaved its contents onto the cobbles. A ruffly skirt printed with pink peonies, a jacket to match. A pleated skirt, a crisp white blouse. Someone had waited all her life to come to Rome, bought a new spring wardrobe, and now this. It made me sad. Back to the police station I went, but the treasure trove had been picked clean by the time an officer appeared.

The Sentries kept coming. One was a black woman in a furry white jacket and running shoes. She held a blue coat over her arm and spent a motionless hour on the Sentry bench, head craned to the west. Then she unglued herself from the bench and was gone.

In May I wandered off the piazza and into one of the dark alleys I’d never before set foot in. Girls of every race sashayed down the streets in zebra boots, blond wigs, corsets, and hot pants. But of course! That explained the Sentries.

But mysteries remained. Why was the woman in the pink beret crying on a stone bench one cold day in January? Why did a fellow survey the piazza at eye level one morning in March and then haul out his unit to urinate in the dwarf palm? Had he simply forgotten about the eyes in the seventy-five windows above him? Who had lost her suitcase? And why do Rome’s nasone never stop running?

The hot nights came back. The Gypsy turned up again to play “My Way.” I wanted to stay and see the whole show over again. But it was time to close the window and go home.

***

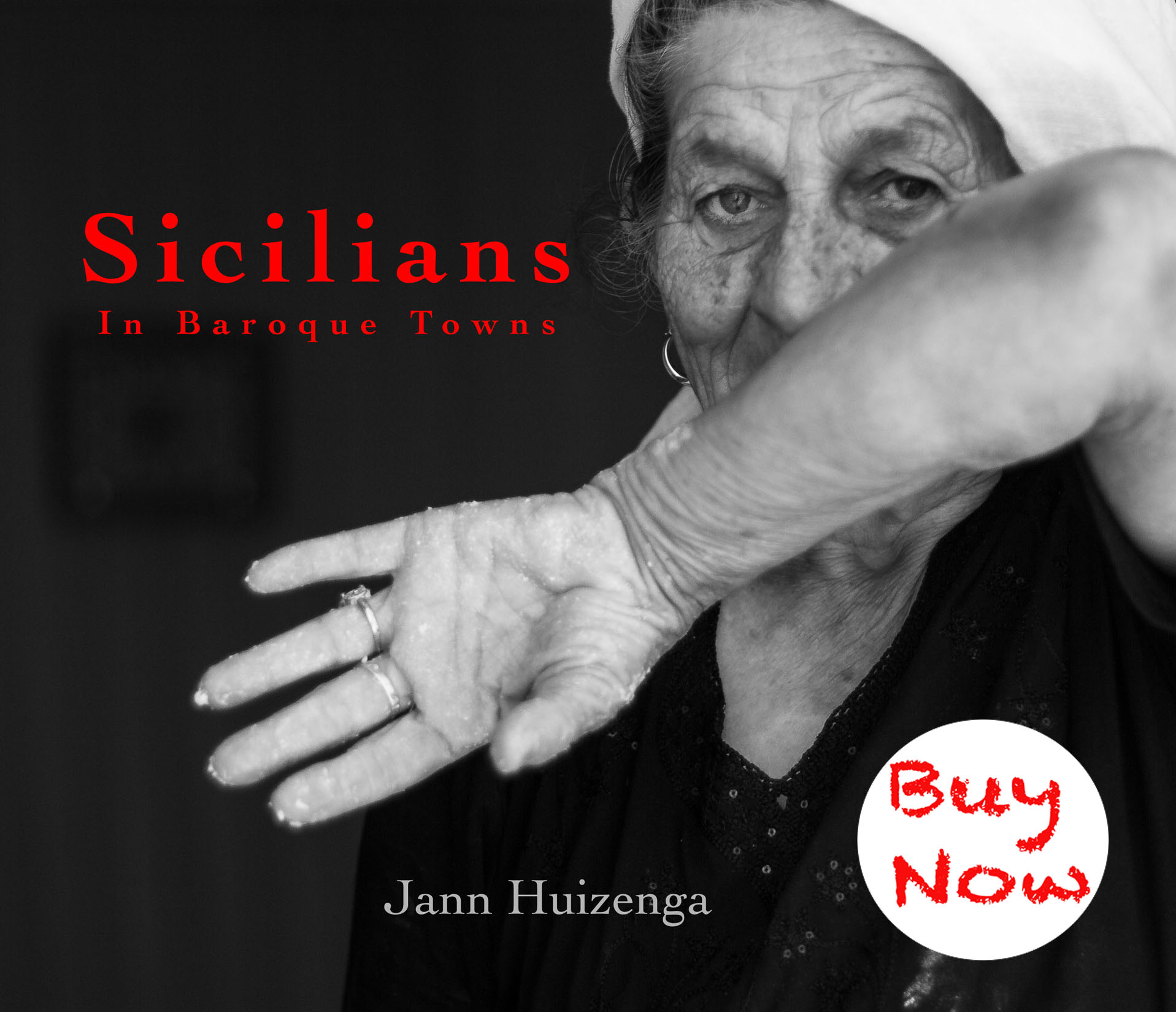

Click here to subscribe to BaroqueSicily.